Robert Hoddle – chains and grids in terra nullius

Preamble

On a recent heritage walk in Lower Plenty-Yallambie, I was asked how colonial surveyors actually measured the Crown Land Portions, and why Martins Lane was called 50 Links Occupation Road.

People looked unconvinced when I talked about surveyors dragging a chain, the length of a cricket pitch (22 yards), through the landscape to make the measurements, which they duly recorded and mapped and that 50 links meant the road was half a chain (11 yards) wide.

Questions followed on where surveyors started measuring from and how it came to be Crown Land in the first place. While I could provide some answers, I made a mental note to research the details.

Accordingly, this article aims to briefly explain the how and why of 1830s surveying in Port Phillip District, as well as providing information on Robert Hoddle’s work and the historical context he operated in. One thing leads to another and the article concludes with the overturning of terra nullius and recognition of native title in Australia in 1992.

Anne Paul, February 2024

Surveyor Robert Hoddle

Most Victorians are familiar with Robert Hoddle as Melbourne’s surveyor, as well as Hoddle Street and the Hoddle Grid. Some will know that he also led the surveying of Crown Land in the Viewbank – Yallambie – Greensborough area, as well as other parts of Victoria and Australia. This was done under direction of the Governors of New South Wales and Port Phillip District, who were granted their power under an Act of the British Parliament of 1787.

Hoddle and other surveyors’ work was based on the presumption of terra nullius and ignored the native title rights of First Nations people to occupy their traditional lands.

Terra nullius – meaning land belonging to no-one – was the legal concept used by the British government to justify the settlement of Australia.

It remained the legal principle on which British colonisation rested until 1992, when the High Court of Australia brought down its finding in the Mabo vs Queensland (No. 2) case, ruling that the lands of the continent of Australia were not terra nullius at the time of settlement. (NLA digital classroom)

Much has been written about Hoddle’s life and his survey work, with research ongoing, especially as more material becomes available online through the National Library’s Trove and the Public Record Office Victoria (PROV).

Robert Hoddle (1794-1881) started as a cadet-surveyor in the British army in 1809 and took part in survey work in Britain and Cape Colony (South Africa), prior to migrating to New South Wales in July 1823. He was appointed an assistant surveyor, surveying in Moreton Bay (Queensland) and country districts of New South Wales, as well as the road over the Blue Mountains. (Hoddle-Colville, B. 2005)

Hoddle came to Port Phillip District with Governor Sir Richard Bourke in March 1837 and was appointed senior surveyor over the existing surveyor Robert Russell. After the separation of the colony of Victoria in 1851, he became Victoria’s first surveyor-general.

There are layers to Hoddle’s life and work, including conflict with Governors, colleagues and others in authority. However, he is recognised for his foresight, resourcefulness and technical skills, including the provision of wide boulevards from the city to suburbs, as well as designing Melbourne’s city grid and wide streets. (Tipping, M. 1969)

Melbourne town

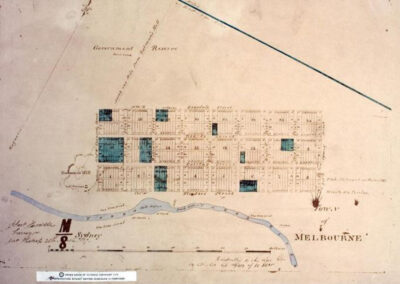

Hoddle produced a grid plan for Melbourne, using the survey work of his predecessor Robert Russell, which he apparently didn’t acknowledge. The streets were surveyed 1½ chains (99 ft) wide, the blocks were 10 chains (660 ft) square, with allotments 1 chain (66 ft) wide. Little streets of ½ a chain (33 ft) wide were inserted east-west through the middle of the blocks, to allow for rear access.

The wide streets were named after Port Phillip identities, politicians and royalty. The main north-south road, to the east of town, was named after Hoddle.

Hoddle was appointed auctioneer at the first sale of Crown Land on 1 June 1837, and he sold half-acre allotments averaging just over £35 an acre. His commission was £57 12s. 7d., and he bought two allotments for himself costing £54.

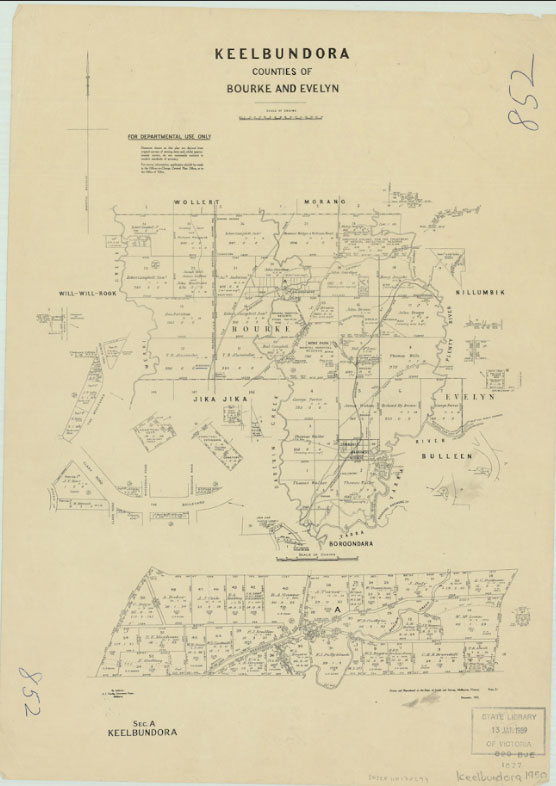

However, with Port Phillip District’s increasing settlement and importance, there was growing pressure to release more land for sale. By 1838 Hoddle, with his assistants and team of convict labourers had surveyed Geelong and other areas of country Victoria, including the Parish of Keelbundora in the County of Bourke, which spans the Plenty River-Darebin Creek corridor.

Map: Robert Hoddle’s survey of the town of Melbourne in 1837.

Source: Sydney map M/8 (Victorian Public Record Office VPRS 8168/P2 Historic Plan Collection, Unit 6167, Sydney M8)

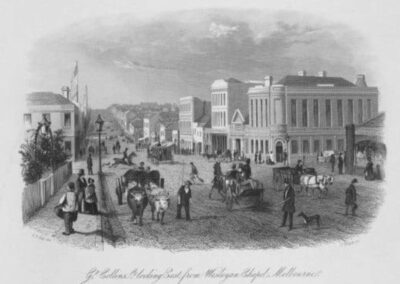

Great Collins Street Looking East from Wesleyan Chapel

Great Collins Street Looking East from Wesleyan Chapel, Melbourne, 1856, Image by ST Gill, engraving by James Tingle, State Library Victoria

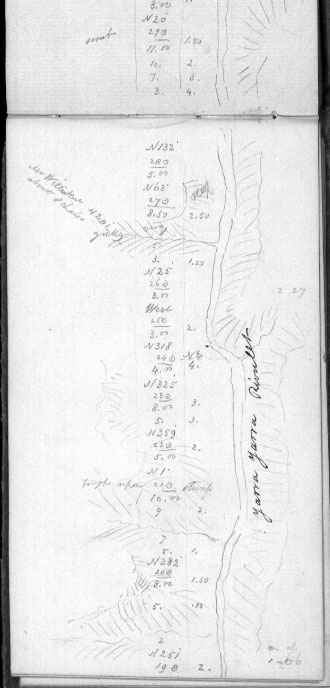

Hoddle’s field notes

Robert Hoddle made consecutive rough maps and notations, along with his measurements in his Field Notes when surveying, including in the Viewbank-Greensborough area and beyond. These have been preserved and can be accessed online via Landata Victoria. The original documents can be viewed at the Public Records Office Victoria. They are not easy to decipher.

Hoddles Field Notes August 1837 along the Plenty River at Janefield. Source: Public Record Office Victoria (PROV)

The first rural land sales were conducted by auction in Sydney on 12 September 1838 and included most of the Crown Land allotments of Keelbundora. They were snapped up by the wealthy and connected, often to be subdivided and resold at substantial profit. So began Victoria’s ongoing boom and bust cycle of land speculation and development.

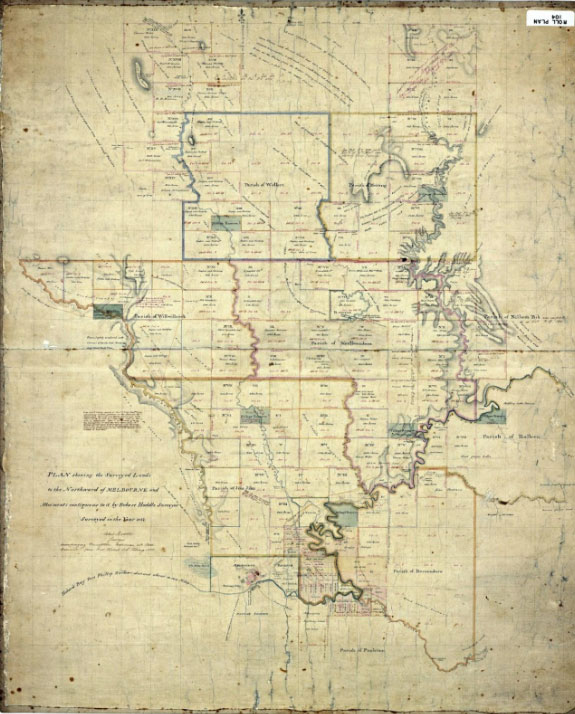

Plan showing the Surveyed Lands to the Northward of Melbourne and Allotments contiguous to it by Robert Hoddle Surveyor 1837. Source: PROV

Map of Keelbundora, derived from original 1837 plan, showing addition of roads, reserves and other features. Source: PROV

Surveying in colonial times

Surveying in colonial Australia was primarily about land sales and settlement, the transfer of Crown Land into private ownership for European settlers and affirming terra nullius. The colonial governors and government viewed the land as belonging to the Crown, not the indigenous inhabitants, nor the squatters who had already occupied some areas.

The key questions I want to address is how Hoddle and other surveyors actually carried out their survey work, and what was involved in creating the Crown Land Allotments that enabled the land to be sold.

Surveying 101 – the Gunter Chain

The Gunter Chain was invented by English clergyman, astronomer and mathematician Edmund Gunter (1581-1626). Gunter’s chain was first used in 1620 and was based on the ancient measure of the breadth of a furrow or plough strip. It enabled land to be accurately surveyed, for legal and commercial purposes, well before the development of sophisticated surveying equipment.

The Gunter Chain measured 66 feet in length. It consisted of 100 links, usually marked off into groups of 10 by brass rings or tags, with the number of points on the tag denoting its position on the chain. (Simpson, M. 2018)

It was the principal means for the linear measurement of land for almost 300 years and was used for surveys in the British Empire. The chains were also used by landowners and farmers, and importantly, to measure the length of a cricket pitch.

The invention of the steel tape in 1867 provided a more convenient and accurate means of measuring large distances and by the early 1900s, Gunter’s Chain had generally fallen out of use.

Gunter’s Chain measurements

1 link = 7.92 inches

25 links = 1 rod (pole or perch) or 16.5 feet

100 links = 1 chain or 66 feet or 22 yards or 792 inches = length of cricket pitch, between the wickets

10 chains = 1 furlong (‘furrowlong’) or 220 yards or 660 feet

80 chains = 1 mile or 5,280 feet or 1,760 yards

10 square chains = 1 acre or 43,560 square feet

Gunter’s surveyor’s chain reputedly used by Robert Hoddle for surveying Melbourne. Source: State Library of Victoria Picture Collection

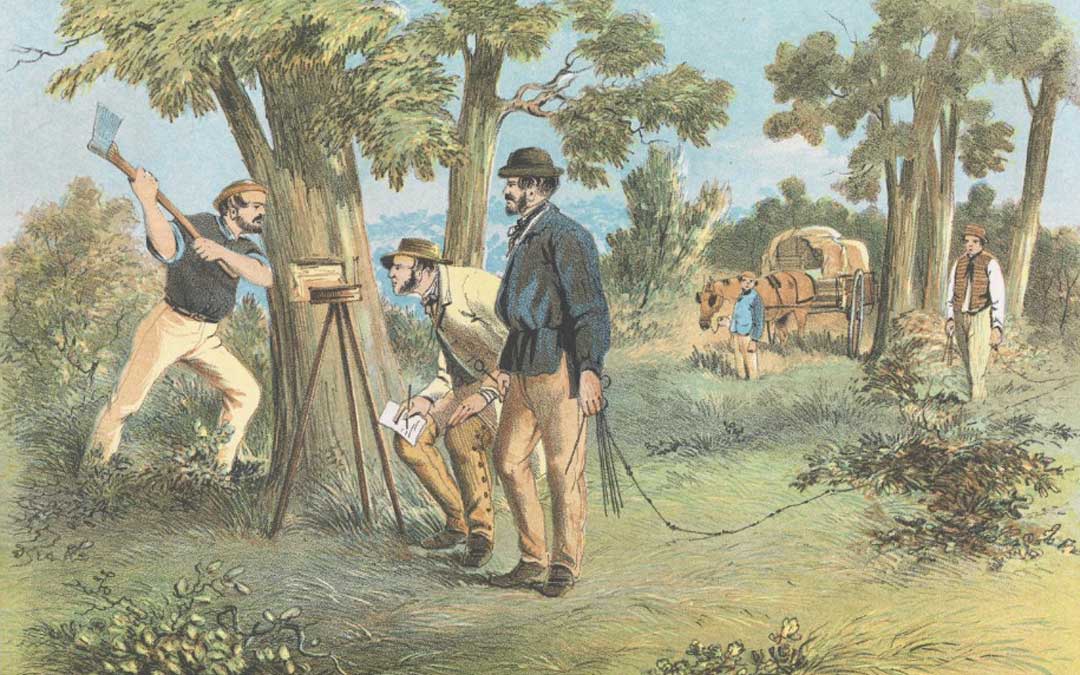

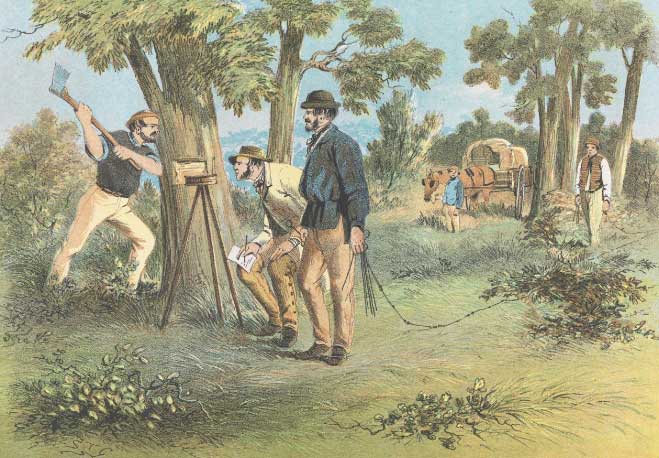

S. T. Gill, Surveyors, 1864. Source: National Library of Australia

Surveyor’s field work

The work of colonial surveyors was very difficult, moving through unknown territory, forests and waterways. As well as surveyor assistants, the early surveyors were assigned teams of convicts.

This drawing by ST Gill is a great image of surveyors at work. Note the Gunter’s chain spread between the blue coat man in the centre and brown vest man to the right in the distance. The axeman is marking or blazing a ‘surveyors tree’, which was then chiselled with Roman numerals.

The Surveyor in Charge, with notebook and pencil in hand, is using a circumferentor, as did Hoddle. It is essentially a large compass with sights, mounted on a tripod. It was used in rural settings to measure horizontal compass bearings relative to magnetic north. Note also the horse and supply wagon to the rear, with the cook or camp man in light blue.

How Gunter’s Chain was used

To measure a section of land, a surveyor marked the starting point with a stake, stretched the chain to its full length, and then placed another stake at the end of the chain to mark the 66 feet. This continued until the desired amount of land was surveyed. The chainman dragged or carried the chain between the stakes, under the direction of the surveyor.

The whole process was repeated for all the points required, and from this it was a simple matter to make a scale diagram of the plot of land. The process was surprisingly accurate.

The stake at the boundary was usually a log, 6ft long in diameter buried 2ft in the ground, chiselled with allotment numbers, with trenches dug to indicate the direction of boundary lines. If available, a nearby tree was blazed, in case the stake disappeared. At locations like a river, a pile of rocks with trenches on the approach and departure side were used in lieu of a stake.

Surveying with the chain was simple if the land was level, but difficult across large depressions or waterways, as it required levelling on sloping terrain.

From 3D field survey to 2D plans and maps

Surveyor’s measurements were recorded in their field notebook, along with sketch maps and notations on vegetation and soil type. The surveyor would then calculate and plot the information from his field notebook including dimension and area, marks such as survey posts and reference trees, the location of waterways and a description of the country.

Plans from the survey were the basis for the issue of title deeds and leases, gazettal of reserves and the compilation of cadastral maps. (Hesse, K. 2018)

No doubt mistakes were made, shortcuts taken and directions overlooked. Some can be understood given the challenges faced with terrain and equipment, while others are difficult to understand.

Robert Hoddle has been praised for his work but also criticised for errors, including overlooking directions from the NSW Surveyor-General’s office to provide an access road or right of way to Crown Land Portions, so that the property owner could access their land.

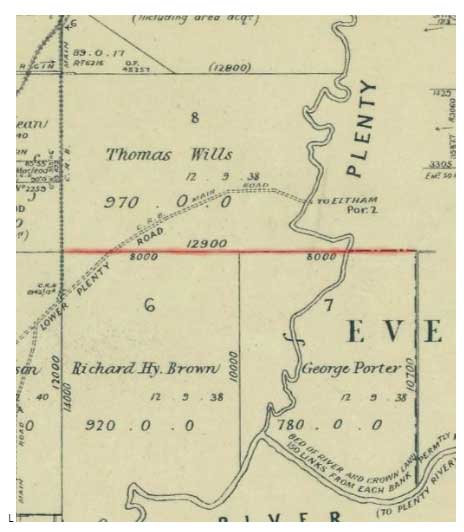

A local example is Martins Lane in Viewbank, the road referred to in the preamble. It forms the boundary between Crown Land Portions 6 & 7 to the south and 8 to the north.

An early map shows Martins Lane was originally called 50 Links Occupation Road. (McBriar, M. 1985) An odd name until the Gunter’s Chain Links and Hoddles road reserve omission are considered. Accordingly, a ½ chain (50 links) wide section was excised off Portion 6 in 1840 to enable Portion 7’s owner, George Porter to access his property.

A letter to authorities from Porter in 1841, showed he still didn’t have access, presumably as Portion 6’s owner, Richard Browne had fenced his land to the original survey boundary. The irony is that Porter was one of the few original selectors to actually farm their land, while most just subdivided and speculated.

This was not an isolated case and it ultimately cost the government as they had to purchase land back from landowners to provide road access..

Details of Parish Keelbundora, Portions 6, 7 & 8, with the 50 Links Occupation Rd/Martins Lane shown in red

On the positive, another directive from the NSW Surveyor-General’s office to record Aboriginal place names appears to have been followed by Hoddle and his team, at times. This was decades ahead of Imperial practice elsewhere, and while often suffering distortion in form and meaning, it likely gave us local names such as Warringal, Nillumbik, Keelbundora and Banyule. (Moyal, A. 2017)

Surveying equipment has changed considerably since Hoddle’s time. The Gunter Chain was replaced by steel tape in the 1890s and chain men replaced by linesmen. Professional training of surveyors became mandatory in Australia in the late 1800s.

Today’s recording equipment is sophisticated and aided by GPS, drones and computer software, but at the end of the day, the surveyor relies on his measurements and recordings to transfer 3D into 2D.

And Gunter’s Chain lives on as the length of the cricket pitch.

Image: Steel Surveyors tape Source: Queensland Government

Robert Hoddle’s career

As for Robert Hoddle, he settled in Melbourne, unlike many of his contemporaries who, fortunes made, returned to the old country for their golden years.

With the separation of the colony of Port Phillip from New South Wales in 1851, Hoddle was appointed Surveyor-General. However, he was ‘eased’ out of the office in 1853, to make room for a younger person, after questions of his suitability, age and temperament were raised by Governor Charles La Trobe. (Moyal, A. 2017)

Hoddle married twice and had five children. The family lived in a fine house on the corner of Bourke and Spencer Streets, built in 1842. In retirement he continued his interest in sketching and music, and was also active in the Old Colonists Association, being elected a life Governor in 1873. He died in 1881, aged 87 years and is buried in Melbourne General Cemetery

Photo Robert Hoddle, Hyman’s Portrait Rooms, c1865 and his drawing instruments. State Library Victoria

The legacy of colonial surveyors

The foundation work by colonial surveyors like Hoddle, using the Gunter Chain, enabled the sale, subdivision and European settlement of the colony. Crown Land sales have evolved into the city and suburbs we live and work in, providing homes and opportunity for millions, while glimpses of our First Nations and colonial heritage lie within the landscape.

In addition, the work by Hoddle and his team ensured that all subsequent subdivisions, roads and development since 1837-38, in the surveyed area, have been based on their foundation surveys and the maps created from them. As well, 21st-century technology of digital maps used in computers, mobile phones and GPS navigation, all have their origins in the work done by colonial surveyors like Robert Hoddle.

However, their presumption of terra nullius, on which the British claims to possession of Australia and Crown Land sales were based, did not last. The 1992 High Court of Australia decision in Mabo vs Queensland altered the foundation of land law in Australia by overturning the doctrine of terra nullius and inserting the legal doctrine of native title into Australian law.

From terra nullius to Native Title

As mentioned at outset, terra nullius is a Latin term meaning land belonging to no one. It was the legal principle upon which British colonisation of Australia rested, with the native title rights of First Nations people ignored.

This principle was overturned in 1992, when the High Court of Australia brought down its finding in the Mabo vs Queensland (No. 2) case, that the Meriam people of the Murray Islands, were ‘entitled as against the whole world to possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of (most of) the lands of the Murray Islands’.

In ruling that the lands of the continent of Australia were not terra nullius at the time of settlement and recognising that native title had always existed, the Mabo decision set a precedent in Australian law. This has seen many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups regain rights over their traditional lands.

In 1993 the Federal Government enacted the Native Title Act 1993 (Commonwealth) which established the Native Title Tribunal, with the intention of providing land rights to affirm the High Court’s Mabo decision. The Act gave jurisdiction to the Federal Court to manage applications for recognition of native title. To succeed in a claim, the applicants had to prove continuous connection to land that had, for the most part, been forcibly taken.

However, even if native title was granted, it can be extinguished by freehold title and most leases. In addition, if the rights of pastoralists, mining companies, federal government or private owners come into conflict with native title rights, they supersede native title.

In 1996, in the Wik Peoples vs Queensland case, the High Court of Australia ruled that native title and pastoral rights could coexist, which provided some clarification. In practice though, the reality of the Native Title Act often falls short of the intent of the 1993 legislation. (Supreme Court Library Queensland, 2016).

Nevertheless, in Western Victoria, an encouraging example comes with the 2019 UNESCO World Heritage listing of Budj Bim (Mt Eccles) and Tae Rak (Lake Condah), for their First Nations cultural significance, following the 2007 recognition of the native title rights of the Gunditjmara people.

This listing of Budj Bim as an area of ‘outstanding universal value, integrity and authenticity’ shows what can be achieved through native title recognition, with the honour of UNESCO recognition highlighting the value of Australia’s First Nations heritage.

Locally, historian Mick Woiwod conducted groundbreaking research that helped improve our knowledge of our local First Nation’s history. He wrote a series of important books on the history of the Yarra Valley’s Wurundjeri people, in particular the grim stories of Coranderrk Aboriginal Station in Healesville and around Kangaroo Ground.

Mick believed we needed to know the truth about the lives of Wurundjeri people, both before and after European colonisation. In doing so, he used his research skills and geological knowledge to draw together threads of information, in consultation with Wurundjeri people, to complete the narrative. We are fortunate he shared his wisdom with us.

On the Plenty River, First Nations site identification and interpretation by Parks Victoria, in collaboration Wurundjeri traditional owners, is central to the Plenty Gorge Parklands project. This work builds on the 1991 archaeological assessment of Aboriginal sites in the Plenty Gorge Parklands. (Ellender, I. 1991) There are also many First Nations heritage sites along the Yarra, such as Bolin Bolin and Banyule Billabongs, as well as the lower sections of the Plenty River. (Weaver, F. 1990)

Hopefully, increased knowledge and recognition of our First Nations heritage will strengthen our appreciation of the world’s oldest living culture, deepen our understanding of the impact of European settlement and help build reconciliation. In the shadow of our failed referendum, this awareness through heritage offers an avenue for progress, alongside the Victorian government’s First People’s Assembly and their work towards a Treaty for Victoria.

Finally, the question of the 50 Links Occupation Road, mentioned in the preamble: It was later named Martins Lane, most likely after Dr Robert Martin, a wealth squatter and Port Phillip Society member. He had purchased the adjacent Viewbank property in 1842, after it was bought and subdivided from Hoddle’s original Crown Land Portion 6.

By Anne Paul

February 2024

Acknowledgements

Ian Bryant – For information, maps and advice on the content and direction of the article.

References

Ellender, I. 1991. The Plenty Gorge Metropolitan Park: Archaeological assessment of Aboriginal sites. Board of Works.

Engineering Resource Associates, 2020. The Gunter’s Chain. Online

Hesse, K. 2018. History of Surveying in Australia. Online

Hoddle – Colville, B. 2005. Robert Hoddle: Pioneer Surveyor, 1794-1881. Online

McBriar, M. 1985. Heidelberg Conservation Study Part 2. Historic Riverland Landscape Assessment.

Moyal, A. 2017. Surveyors: Mapping the Distance, Early Surveying in Australia

National Library of Australia. 2023. Challenging Terra Nullius. NLA Digital Classroom

Supreme Court Library Queensland, Sir Harry Gibbs Legal Heritage Centre, 2016. Overturning Terra Nullius – the Story of Native Title

The Gunditjmara People & Wettenhall, Gib. 2010. The People of Budj Bim: Engineers of Aquaculture, Builders of Stone House Settlements and

Warriors Defending Country. em PRESS, Heywood, Vic.

Simpson, M. 2018. Surveyors or Gunter’s Chain. Powerhouse Collection, Online

Tipping, Marjorie J. 1966. Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 1, Melbourne University Press

Weaver, F. 1991. Lower Plenty River Archaeological Survey. Board of Works

Woiwod, M. 2017. Barak vs the Black Hats of Melbourne.

Woiwod, M. 2015. Kangaroo Ground Dreaming.